It seems like it’s a matter of time till Crypto.com Arena (previously known as Staples Center) is filled again with Middle Eastern progressions of oud (lute), durbake (goblet drum), ney (reed flute), and sāgāt (finger cymbals) as part of a Grammy performance. While these instruments were used in Sting’s and Cheb Mami’s "Desert Rose" and featured in their performance at the 42nd Annual Grammy Awards, this time, it will be an artist out of the new cohort of emerging Arab artists that have emerged among a larger subset of MENA (Middle East & North Africa) artists.

Hailing from the region or the diaspora, some artists became viral sensations, several had their faces emblazoned on a billboard in Times Square, and others were signed to major labels. While these achievements were not possible just a few years ago, they could have been attainable twenty years ago.

Arabic Music Moves West

"Arabic Music Moves West" blared an August 11, 2001, Billboard magazine on the front page in big and bold letters. The growing interest in world music and incorporating global influences into pop music reached an unprecedented level. Arabic music from the MENA region was making big waves in the US. The collaboration between Sting and Cheb Mami on the hit song Desert Rose garnered substantial success in both the US and the UK. Two of world pop's brightest stars, Algerian artist Khaled and Egyptian artist Hakim, were set to embark on their first extensive U.S. tour. Mainstream artists like Jay-Z incorporated Arabic music into their songs. His track "Big Pimpin" contains a sample of "Khosara Khosara," performed by Egyptian Abdel Halim Hafez, and Aaliyah’s "Don’t Know What to Tell Ya" is sampled from "Batwanes Beek" by Algerian Warda. An explosion of Arab music was bound to happen, right?

(L-R) Billboard magazine front page on Aug. 11, 2001, versus Billboard magazine article on Dec. 29, 2001 (source: billboard.com, archive: worldradiohistory.com).

A few months later, on Dec. 29, 2001, Billboard published its annual The Year in World Music report (kind of like the Spotify Wrapped of the print-age), titled "Arabic Suffers Setback While Bollywood Travels On." The tragic events of Sept. 11, 2001, put a quick halt to the momentum of Arab music's popularity in the West, and in the intervening years, overlapping factors, including lingering anti-Arab sentiment and cultural barriers, made it harder for Arab artists to find mainstream success in the West. Yet, Arabic music remained a source of inspiration and influence for many Western artists from Beyoncé to A$AP Rocky, whose track "1 Train" features a looped instrumental sampled from Syrian Assala Nasri’s "Mashet Snen."

While the music of diasporic Arabic artists such as DJ Khaled, French Montana, Belly, and Ali Gatie, which have achieved chart-topping success in the US, may not follow traditional Arabic styles, it nevertheless reflects some aspect of their cultural heritage. With the recent rise of K-Pop, Reggaeton, and Afrobeats in the West, glocalization is encouraging emerging artists to fearlessly implement Arabic elements in their music and still reach global audiences.

The New Generation

Digital proliferation has reversed the artist-fan relationship. Today, people consume music first and become fans second. Songs get included in short-form videos on social media and streaming platforms, racking up millions of streams from global audiences, whether the listener knows who the artist is or not. Consequently, a new wave of Arab artists is coming from the MENA region and the diaspora, creating a global impact in the early stages of their careers. In fact, Spotify’s Fan Study reports that approximately two-thirds of new artists discovered in the MENA region originate outside their home country.

The MENA region is home to diverse cultures, dialects, and music genres, including many types of Arab music, which is itself an umbrella term that embodies a variety of sounds created and homegrown in different MENA countries. For instance, Darija from Morocco, Pop primarily from Egypt and the Levant, Maharaganat from Egypt, and Khaleeji from the Gulf countries. Yet, there’s a genre fluidity within the region, and there’s no one way that music travels.

Arab music diversity is evident in the music of up-and-coming artists who employ distinct approaches to music, ranging from the otherworldly melodies of traditional Arab music to the lively rhythms of contemporary Pop and Hip-Hop. Some artists primarily sing in Arabic, such as Palestinian Pop artist Elyanna, who is scheduled to perform at Coachella in April. Other artists take a bilingual approach, like Egyptian Hip-Hop artist Felukah, who brings the Nile to New York. Artists like Moroccan ABIR, meanwhile, mainly sing in English and also use Arabic instruments in their music, as seen in her EP Heat.

MENA artists create music that reflects the many influences and experiences shaping their lives. For instance, Bayou fuses the musical heritage of the Middle East with elements of Pop and R&B. As an Egyptian who has lived in Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and the US, he addresses topics including third-world culture kids, social norms, and pop culture references from the region. Bayou's bilingual approach appeals to his 337K Spotify monthly listeners who reside in the West and in Western Asia. With a playlist reach of 327K, Bayou is really speaking to the global citizen.

Although there is a debate regarding the fairness of the streaming model, it certainly has democratized music consumption, creating greater opportunities for artists who may not appeal to the typical MENA listener. For example, Lo-Fi and Saudi Pop artist Mishaal Tamer made history as the first Saudi artist to sign with RCA. Despite being based in Jeddah, his statistics suggest that he has a strong Western influence in his music and style: 5.6M+ Pandora streams, 15.4M playlist reach, and 991K global Spotify monthly listeners from countries like the US, the UK, Germany, and India.

Going Viral: The First Step Toward Stardom

There’s no doubt that TikTok has become a vital tool for artists to reach wider audiences. However, the idea of Arab artists launching a music career from social media is still new. In 2020, Jordanian artist Issam Najjar went viral on TikTok with his hit "Hadal Ahebek," which has been Shazam'd 4.6M times and used in 647K+ videos on TikTok. The song became the first Arabic song to peak at No. 1 on the Shazam Global charts and Spotify’s Viral 50 and Top 200.

In 2021, Najjar signed with Universal Arabic Music and collaborated with big acts like Loud Luxury and Alan Walker. Although he solely sings in Arabic, he has 852K Spotify monthly listeners located in trigger cities, including Mexico City, Jakarta, and São Paulo. Nevertheless, it seems like he’s appealing to radio stations in Canada. For instance, in the last 28 days, his music was played 284 times on Canadian stations, with an average of 11 spins per day.

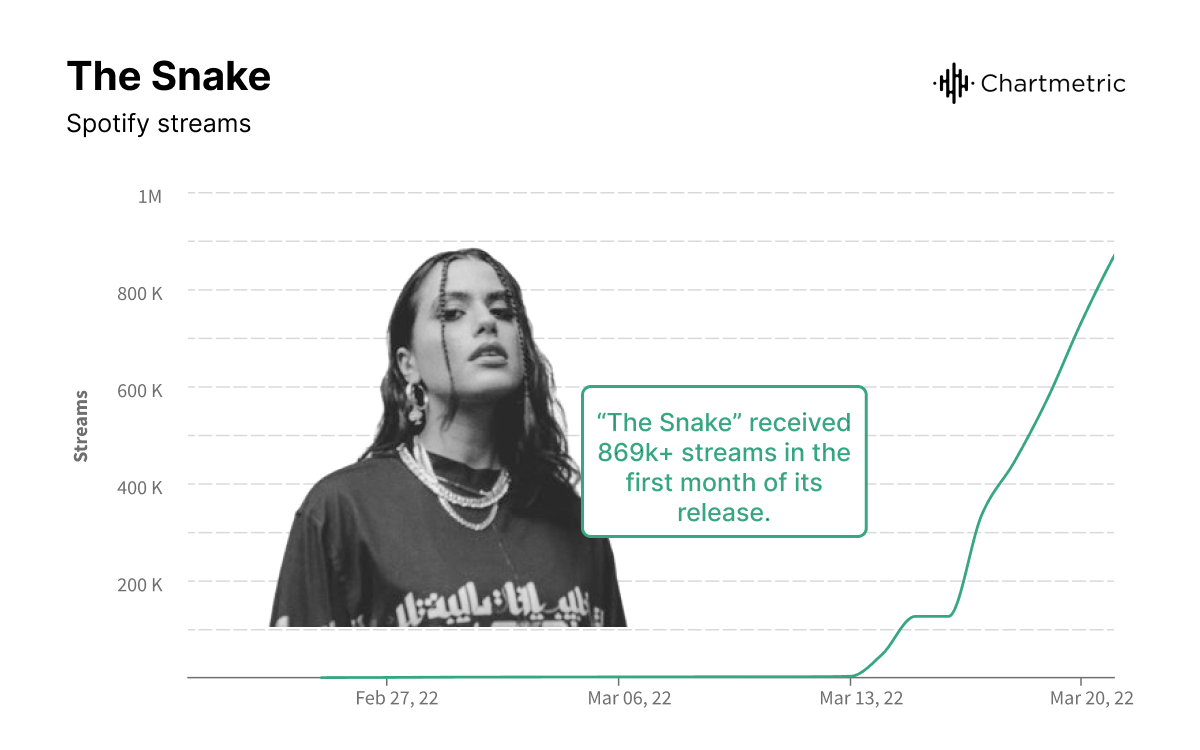

On Feb. 22, 2022, London-based Palestinian-American artist Lana Lubany released her first bilingual song in Arabic and English, "The Snake." However, just the existence of a song on streaming platforms wasn’t enough for it to take off. Three weeks later, on March 11, Lubany posted a TikTok video of her mom’s reaction, which went viral. On March 23, it surpassed 1.1M Spotify streams. The track entered the Viral 50 in 17 countries, peaked at No. 1 on Spotify playlist Fresh Finds (1.2M followers), and was added to playlist big on the internet (3.1M followers). The video gained 7.4M+ views and surpassed 9.6M streams on Spotify. Today, Lubany has 600K monthly listeners, 438K TikTok followers, and the beginnings of a sustainable music career.

One Global Community

The online world has facilitated Arab artist discovery and collaboration, resulting in a sense of community united by the vision of taking Arab music global. This has led to healthy competition among emerging Arab artists, motivating them to improve their sound and providing them with exposure and collaboration opportunities. Spotify’s playlist Arab X, for instance, celebrates global crossovers by or with Arab artists. The frontline playlist has 133K+ followers and mainly features Pop and R&B/Soul tracks by emerging Arab artists. For example, "I Guess" by Saint Levant and Playyard features vocals from emerging Arab artists Bayou, Zeina, and Lana Lubany. It was listed on 28 New Music Friday playlists, including both in the US and the UK, eventually surpassing 6.3M Spotify streams and 49K Shazams.

@saintlevant i love my friends #tiktokarab #fyp #middleeastern #arab

♬ original sound - Saint Levant

Crossing Over

The process of crossing over to Western markets has always been influenced by Western listeners' preferences and their desire to engage with music from different regions. Legendary Arab artists, such as Egyptian Umm Kulthum, Lebanese Fairuz, and Cairo-born French-Italian singer Dalida, were already global in the '60s and '70s.

(Left) New Album Releases section of Billboard featuring Fairuz’s album published Sept. 30, 1967 (source: Billboard.com, archive: Entertainment Industry Magazine Archive). (Right) New York Times article covering Fairuz’s concert at Avery Fisher Hall (now known as David Geffen Hall) on Oct. 1, 1971 (source: New York Times, archive: New York Times’ Time Machine).

In the past, the conventional method for launching an artist involved building a solid local market fanbase before attempting to expand globally. International collaborations have always been the ticket for broadening the reach, and several well-established Arab artists of the past few decades have attempted to break through in Western markets, mostly through collaboration. Despite excelling in the region, their success was limited to the Arab diaspora.

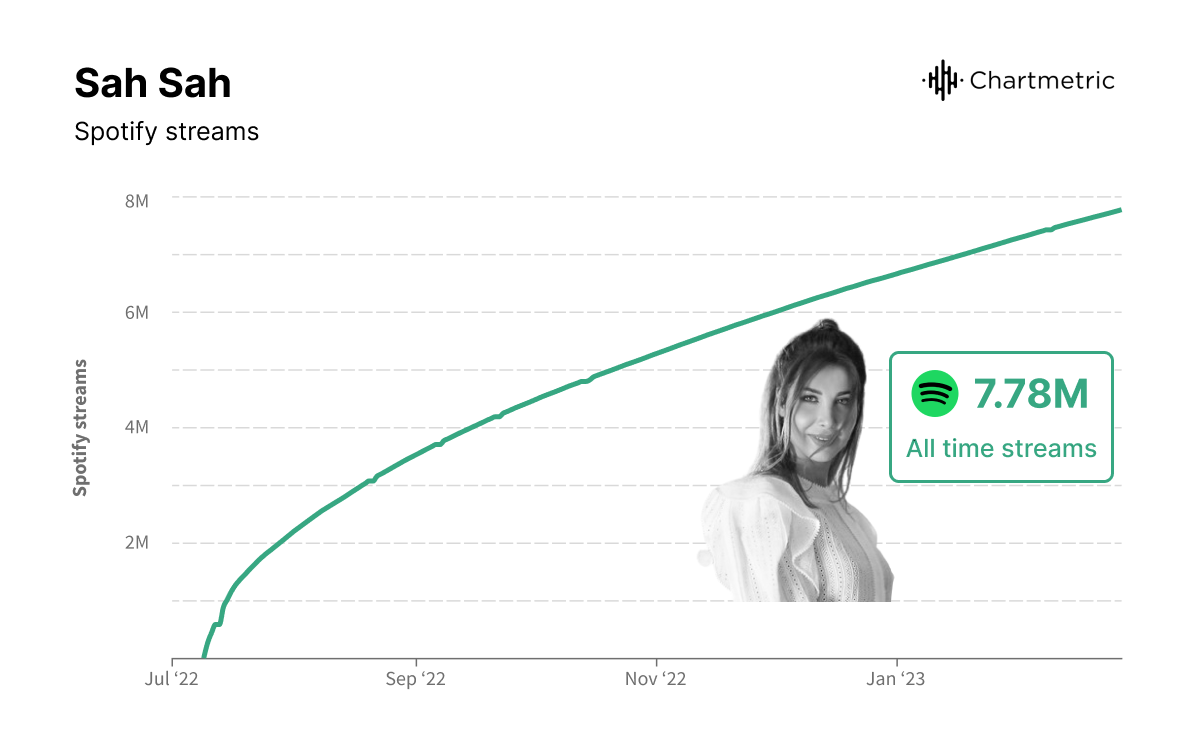

Last summer, Lebanese superstar Nancy Ajram made history with her Marshmello collaboration, "Sah Sah." The Arabic language song became the first Arabic song to reach the Top 10 on the US iTunes Electronic Chart, peaking at No. 9 and No. 38 on the Billboard Hot Dance/Electronic Songs Chart. "Sah Sah," which translates to "wake up" in Arabic, grossed 50M views on YouTube, 8M streams on Spotify, and 72K Shazams.

But it didn’t take long for another Arab artist to hit the first spot. This month, Skrillex teamed up with emerging Palestinian artist Nai Barghouti on a joint track, "Xena." Skrillex's Bass and Techno sound is joined by Nai, who sings a traditional folk wedding song. The song peaked at No. 1 on the iTunes Electronic Chart in the US, Canada, Japan, Taiwan, Armenia, and Guatemala and debuted at No. 21 on Billboard’s Hot Dance/Electronic Songs chart.

Crossing over also happens as a result of TV and movie syncs, which help introduce Arab music to new audiences. Western TV shows like Hulu’s Ramy and Disney+'s Moon Knight feature legendary artists like Lebanese Sabah and Algerian Warda and established regional artists like Egyptian Ahmed Saad and Wegz. Who knows, maybe Warda’s "Batwanes Beek" will be the next "Running Up That Hill"?

The Arab Diaspora

The Arab diaspora is dispersed throughout many nations, primarily in the United States, Brazil, France, Canada, Australia, and Germany. Those who fled war, uprisings, and refugee crises feel nostalgia and a longing to obtain a sense of their native lands. Listening to Fairuz or to the old classics in the morning goes hand in hand with morning Arabic coffee. When they gather for celebrations, besides enjoying the appetizing cuisine, they celebrate their culture by listening to music from their home countries, including timeless Pop songs like Amr Diabs’ "Ya Nour El Ein," and forming a circle and dancing dabke (Levantine folklore dance).

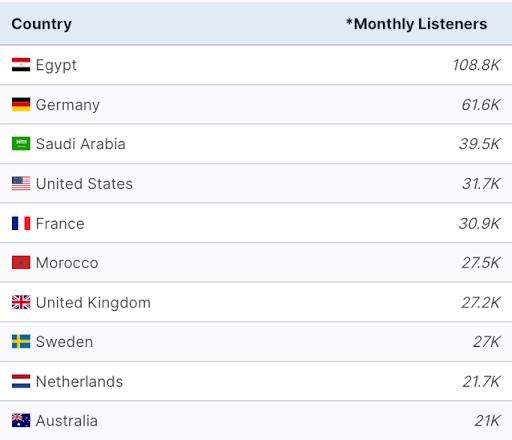

Well-established Arab artists have international tours for their diasporic communities, performing in concerts and banquets to connect with fans who may not have access to live performances in their home country. To emphasize this, let’s look at the audience map across YouTube and Spotify for the Lebanese superstar Elissa, the No. 1 Arab artist on Chartmetric. Given that YouTube is the most widely used streaming service in the MENA region (reflected in the gap between YouTube views and Spotify streams for "Sah Sah"), the figures show that she has a significant local audience across the region. On the other hand, her Spotify monthly listeners are comparatively much smaller and more global, suggesting they likely represent the Arab diaspora.

Elissa’s audience on Spotify (left) and YouTube (right).

Fairuz Unifies Arabs Worldwide

The legend Fairuz, one of Lebanon’s national symbols, holds a special place in the hearts of many Arabs in the region and the diaspora. Her music serves as a unifying force for Arabs all over the world. With a career spanning 60+ years, she is one of the best-selling music artists in the world. Seven countries out of Fairuz’s Top 10 monthly listeners are outside the region, and her 126.5M YouTube views are from audiences worldwide, with a daily view count of 629K. She has largely disappeared from public life in recent years, but her soaring voice remains ubiquitous every morning from radios to street cafes across the region. Fairuz is so popular that there are endless YouTube and Spotify playlists of “Fairuzyat.” Just over the last year, she was played 882 times on foreign radio stations, mostly in France, Belgium, and Canada.

Furthermore, emerging Arab artists usually thrive in diasporic communities. Arab diasporic communities often host cultural events and performances, providing opportunities for emerging artists to showcase their talent and gain exposure. With endeavors from diasporic Arab entrepreneurs like Empire Founder and CEO Ghazi, Universal Arabic Music Founder and CEO Wassim ‘Sal’ Slaiby, Beatstar Founder and CEO Abe Bashton helping Arab artists export their music to global audiences, there’s no doubt that the future seems bright.

Where Does Arab Music Go Now?

Even though 23 years have passed since "Desert Rose," it's still charting on Shazam, featured in 33K+ TikTok videos, and has 18M million views in the last month. Based on the volume of streams and the global organic growth of the region’s rising talents, Arab music is making its way, once again, to global stages. These emerging Arab artists are just a glimpse of the vast cohort of talented individuals making their mark in Western markets.

The question of whether to perform in Arabic, in English, or in both languages will always accompany those who want to cross overseas. Yet the most important question is: At what point does excessive Western influence impede the use of Arabic, and how can Arab artists authentically maintain their cultural identity while looking toward the West?